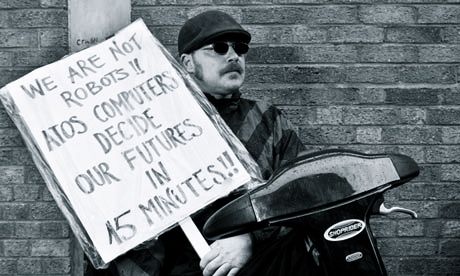

In the first of a new series, we offer up a perspective on how guerilla policy – policy developed opening, collaboratively and consensually by the people affected by a particular issue – is influencing mainstream policy development. In this post, we argue that the sustained pressure from the grassroots campaign Spartacus has kept the Atos Work Capability Assessment on the mainstream political and media agenda long after other issues have fallen by the wayside.

There has been much debate in the blogosphere and on Twitter over the past week about the supposedly minor changes to the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) that come into force on 28th January 2013. Spartacus the grassroots movement of disabled people, whose Responsible Reform report on welfare reforms broke through last year, has launched a campaign - #esaSOS, to try and prevent any changes from coming into force. The Spartacus campaign is an authentic and open campaign based on real life experiences, powered by social media and a reaction against policy makers and politicians not listening.

The WCA is the flawed fitness to work test that was introduced under the last Labour Government and assesses whether disabled people can receive Employment Support Allowance (ESA). The Coalition has expanded the WCA as part of their ‘welfare reforms’ designed to tackle long term worklessness. Atos who have a £100 million a year contract to undertake these assessments have been widely discredited for the role that they play.

The #esaSOS campaign has argued that “although these (WCA) changes have been advertised as small ‘amendments’, they will in fact have a huge impact on the way people’s illnesses and disabilities are assessed”. The campaign has argued that the changes will result in false assumptions being made about an individual disabled person’s circumstances:

“This assessor doesn’t just need to look at your current difficulties. For example, they can also imagine how using an aid (e.g. a wheelchair) might improve your ability to work and make a judgment based on that – without even asking your opinion!”

The changes take little account of pressures to reduce spending and structural reform elsewhere in the health and social care system. Pseudo Deviant writing on Pseudo Living makes some particularly pertinent points about the availability of wheelchairs through the NHS: “Bitter experience has taught me that the NHS doesn’t give wheelchairs to a lot of people who would benefit from them.”

The second concern raised by the #esaSOS campaign has been the separation of physical and mental health:

The government is also trying to change the way people’s conditions are assessed by dividing health problems into two separate boxes: ‘physical’ and ‘mental’. When looking at what tasks people can do, only the ‘physical half’ of the test will apply to those with physical disabilities. The same goes for the effects of treatment: for e.g., if you’re taking mental health medication, only mental health side-effects will be looked at.

Early Day Motion 295, which has been signed by 118 MPs, deplores the Atos WCA arguing that it is flawed because 40% of appeals are successful but people have to wait six months for them to be heard. It points out the tragedy that over 1,100 claimants have died while under compulsory work related-activity for their benefits and that a number of those found fit for work and left without income have committed or attempted suicide.

In a House of Commons debate this week called by Michael Meacher MP, on the Atos Work Capability Assessment, there was cross party criticism of Atos and the way the WCA is being implemented. Meacher described three cases which illustrated how ‘how extreme is the dysfunction and malfunctioning of the Atos assessments’, including this one:

“The first example concerns a constituent of mine who was epileptic almost from birth and was subject to grand mal seizures. At the age of 24, he was called in by Atos, classified as fit for work and had his benefit cut by £70 a week. He appealed, but became agitated and depressed and lost weight, fearing that he could not pay his rent or buy food. Three months later, he had a major seizure that killed him. A month after he died, the DWP rang his parents to say that it had made a mistake and his benefit was being restored.”

MPs from all parties, speaking in the debate, documented examples of individuals who have experienced real hardship, fear and distress as a result of the WCA. Conservative MP Heather Wheeler asked whether Atos reviewed the cases of those people who dropped “down dead within three months of being told they are fit for work”. “At what point do we say that this isn’t working?” she asked. Caroline Lucas of the Green Party also condemned the “humiliating and demeaning” process, which “makes sick people even sicker”. Would there have been this parliamentary debate if it weren’t for the sustained and committed grassroots campaign against this policy?

The sustained pressure from the grassroots Spartacus campaign has ensured that the WCA and the reforms that come into force this month have remained in the spotlight. The campaign is an example of what we have termed guerilla policy – a different approach to developing policy that is a reaction to the traditional closed approach centred on a relatively small circle of politicians, senior civil servants, think tanks and lobbyists. The question for policy makers is how long can they sustain the WCA policy in the face of this growing movement against it?

[...] has continued to show how social media can mobilise a movement for change. In a post this week, GuerillaVoice: #esaSOS, we argued that this campaign was an example of guerilla policy – “policy developed opening, [...]

[...] reflected on how the grassroots campaigns against the WCA changes represented an example of guerilla policy in action. Many speakers in the Parliamentary debate on the reforms were heavily informed by groups such as [...]