I have argued before that the usual left/right distinctions can be meaningless in education. Instead of a left/right spectrum I preferred this 2-dimensional version [below] which separates the issues of what should be taught (the content axis) and who it should be taught to (the entitlement axis).

Lazy thinking (shown by those who look only at positions on the red line) suggests that a traditional curriculum should be accompanied by an elitist view of who is to learn it, and an egalitarian belief that everyone is entitled to a high quality education should be accompanied by trendy beliefs about content and pedagogy which completely undermine any notion of what a high quality education actually is. Normally this “red line” thinking results in smearing supporters of a knowledge-led curriculum and traditional teaching as right-wing advocates of inequality by refusing to acknowledge the existence of the top-right quadrant.

Yesterday, it led to confusion over the bottom-left quadrant. Two right-wing publications (the Telegraph and the Spectator ; there may have been others) celebrated the work of Robert Plomin who was apparently visiting the UK and popping in on the DfE. An American psychologist, Plomin was reported to have concluded that GCSE results depended more on genes than teaching. These conclusions were music to the ears of those of an anti-egalitarian bent. We no longer have to worry about policy or poverty causing educational failure if it is genetically determined. We no longer have to worry that privilege (say, a place at Eton) provides access to educational advantage if it is of limited effect compared with genes. We can even dismiss differences in attainment between races and classes if they are a result of a genetic legacy rather than social disadvantage. I’ll return to the issue of how Plomin’s data should be interpreted later, but the interpretation the man himself gives places him firmly on the bottom half of my diagram. What was missed, however, was that far from being a conventional educational conservative in the bottom right quadrant, his views on the curriculum were anything other than conservative. According to the abstract quoted in the Spectator article, Plomin and his co-authors have concluded that:

We suggest a model of education that recognises the important role of genetics. Rather than a passive model of schooling as instruction (instruere, ‘to build in’), we propose an active model of education (educare, ‘to bring out’) in which children create their own educational experiences in part on the basis of their genetic propensities, which supports the trend towards personalised learning.

This is hard to distinguish from educational progressivism. The genetic twist has caused some confusion. Try replacing “genetics” and “genetic propensity” with “class” and “background” and you’d have a sentiment consistent with many a supporter of progressive education. Try replacing “genetics” and “genetic propensity” with “motivation” and “children’s interests” and you’d probably mop up the rest of the progressive educationalists. Plomin is in the bottom left corner of my diagram, rejecting traditional education. Being off the red line means we wouldn’t identify him with today’s supporters of progressive education and we don’t immediately recognise his position; it is rare these days. It would have been common before the second world war when a concern with the genetic material of society was as much a mark of the “progressive” left as the far right with which we tend to associate it today. Diane Ravitch’s book “Left Back” locates the American educational reforms based on psychometrics firmly within the progressive tradition in education and in that era there were no shortage of political “progressives” who advocated both progressive education and eugenics.

Of course, this all means that while a certain type of right-winger, presumably reflected in the sympathies of the Telegraph and the Spectator, had every reason to love the anti-egalitarian implications of what Plomin said, even though there really was little in it that would chime with Michael Gove’s educational policies which have tended to emphasise the importance of both traditional education and academic education as a universal entitlement (i.e. the top right corner). Moreover, the idea that schools and teachers have far less influence than genetics would also lessen the appeal of policies such as free schools, academies, league tables or even performance-related pay. There’s little point judging schools or teachers on results, or putting resources into new types of schools, if it is accepted that genetics is far more important in determining outcomes. Gove has remained loved by educational conservatives largely because he has been so hated by educational progressives and neither group likes to acknowledge any position off of that red line. But Plomin and Gove are at opposite corners of the diagram and neither are on the red line on which “normal” education debate in the media takes place. Inevitably this led to some confusion and I had a great time on Twitter yesterday, after @toryeducation tweeted a link to the Spectator article, explaining just how much Plomin’s views disagreed with, or undermined, Gove’s.

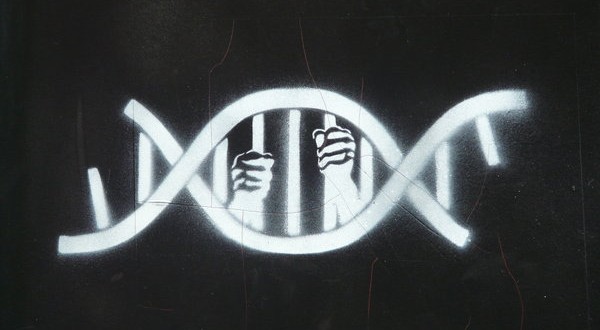

With regard to my views on Plomin’s research, his genetic determinism strikes me as very similar to the economic determinism we get from the political left. It is simply not enough to say that using present data and statistical techniques based on correlation we can conclude what can or cannot be changed. We can only say that, at present, there is greater correlation (controlling for other factors) with one factor than another. If at present our schools aren’t making much difference then it doesn’t mean they never can. Indeed, it’s easy to imagine some interventions that if put in place would make genetically similar children get widely different results thereby completely changing the relative effects of environment and genes found in the data. The data doesn’t even imply that the causation works directly from genes to results without involving any environmental factors. If identical twins are treated more similarly than non-identical twins by parents or schools then the effects of that treatment may well be similar where there is genetic similarity, but that does not mean the genes have directly caused the effects. It is very easy to assume that if statistical techniques are sophisticated enough then they eliminate all the issues of correlation versus causation that we argue over in simpler statistical models, yet correlation is the basis of all these methods and, as ever, it does not imply causation. I don’t believe genes are destiny any more than social class is. If teachers are currently not making enough difference to our students to show up in this data then I suggest we try to make more difference, not give up on that possibility.

And now I need to find just where I put my copy of Gattaca.

Courtesy of Andrew Old at Scenes from the Battleground

Comments

No responses to “Kids are failed by The System, not their genes”